Claim: Kurds deprived of political representation

Ex-mayor of majority-Kurdish city in southeastern Turkey claims “young people” are deprived of political representation

On 21 October 2016, the Economist published an article about the Kurds in Turkey in which it was claimed that they do not have political representation. The article presented this claim as the underlying logic of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party’s (PKK) fight against the Turkish state.

Sabri Ozdemir, the ex-mayor of the southeastern Turkish city of Batman, who was suspended due to allegations of having ties to the PKK, was quoted in the article as saying “If you deprive young people of political representation, they have no choice but to wage violent struggle.”

Although Ozdemir presented the “violent struggle” in Turkey as a new circumstance by linking it to the recent suspension of mayors – a move which he considers as depriving “young people” of political representation – the PKK’s fight against the Turkish state dates back to the 1980s.

The PKK is a Marxist-Leninist militant organization – listed as terrorist group by Turkey, the US, NATO and the EU – that seeks to impose its ideology on Turkey’s majority-Kurdish southeast.

It is true that the Kurds were deprived of political representation in Turkey, especially until the 2000s. Kurdish political parties such as the People’s Labor Party (HEP), the Democracy Party (DEP), the People’s Democracy Party (HADEP) or the Democratic Society Party (DTP) were either shut down or at least brought before the Constitutional Court of Turkey to be shut down.

Even the words ‘Kurd’ or ‘Kurdistan’ were not welcome in the Turkish state’s view even at the beginning of the 2000s. In 2002, for instance, a prosecutor wanted to sentence a 14-year-old student to three years aggravated jail time because they replaced the word Turk with Kurd in Turkey’s founding father Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s saying “How happy is the one who says, I am a Turk!”

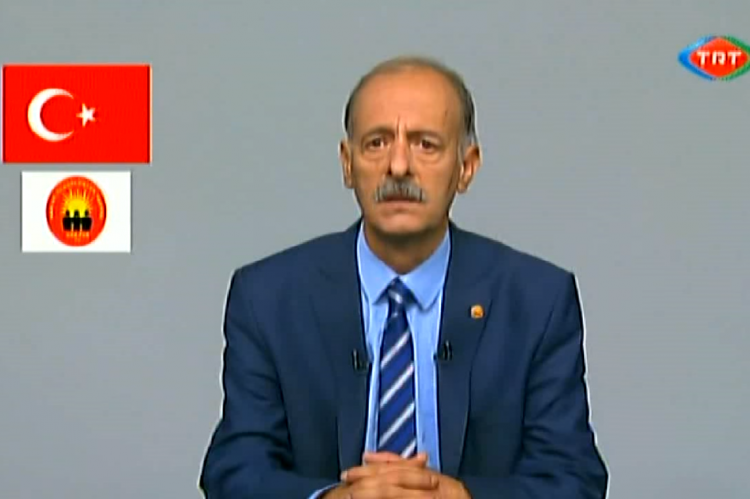

The 2000s, however, were marked as a decade in which the Kurdish movement found much better conditions for political representation. For instance, election propaganda was officially allowed to be delivered in languages other than Turkish in 2010. HAK-PAR’s chairman gave his electoral speech in Kurdish on the state channel TRT for the first time in Turkey’s history.

Hinting at the debate on whether or not the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) should be closed for its support for the PKK, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said in a recent interview that he is completely opposed to closing political parties. “Party closing should never be an option. But the deputies, mayors or others who commit crimes must endure the consequences.” The ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) founded by President Erdogan also faced a closure trial in 2008 but survived it.

In 2014, a political party that included the word ‘Kurdistan’ in its name was established for the first time in the history of Turkey. The Turkey Kurdistan Democrat Party (TKDP) advocates the idea of an “independent Kurdistan,” but it did not participate in any elections yet. Similarly, the HDP’s passing of the 10 percent threshold in the June 7 elections last year was hailed as a crucial democratic achievement since it was the first time a pro-Kurdish party surpassed the threshold.

Another important political event that took place in 2014 was the presidential election that was held by popular vote for the first time in Turkey – a post which was previously elected by the Grand National Assembly. The other first in the election was that a Kurd, Selahattin Demirtas, co-chair of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), was one of the three candidates running for president. Demirtas gained nearly 10 percent vote in the election.

Please click here for a timeline that shows the democratic developments in Kurdish rights in Turkey.

Furthermore, statistics challenge the common understanding that the HDP is the only pro-Kurdish party, hence the unique representative of the Kurds. As opposed to 62 percent of Kurdish votes the HDP gained in the June 7 general elections, for instance, the ruling AK Party’s share was 29 percent. Also, the AK Party had 34 percent vote from the Zazas – people who speak Zaza and are widely accepted as part of the Kurdish nation – whereas the HDP’s share of Zaza votes was 30 percent.

The HDP, which gained around six million votes across Turkey in the June 7 elections, lost nearly a million votes in the November 1 snap elections. Analysts pointed out the HDP’s support for the PKK’s proclamation of “autonomy” or “self-rule” which resulted in trenches dug by the PKK in the middle of majority-Kurdish cities of Turkey, the return of violence and a worsening economy in the region accordingly.

The second claim in the article was that the suspended mayors did not have any links with the PKK. Responding to the AK Party’s Kurdish deputy Orhan Miroglu’s accusation that those municipalities “had not been governed by elected officials, but by the PKK, and no democracy could have allowed that,” Sabri Ozdemir “insists this is false,” without giving further explanation.

However, there is evidence that indicates a mutual relationship between the evicted mayors and the PKK. Arms and explosives were reportedly found in the HDP municipalities. Some examples are as follows:

1) "Van police department announced that the police forces seized 100 kilograms of ammonium nitrate, 26 detonators and 20 large batteries that are used in bomb making from a truck owned by the Van municipality," TRT World reported.

2) In Van's Ipekyolu district, 38 kg ammonium nitrate and 160 g A4-typed explosives were placed by the PKK on a road which students used to go to school. It was later found out that the HDP municipality helped the PKK militants to cover the trap by putting paving stones on it.

3) Police conducted a raid on the HDP's Sirnak municipality and found 19 howitzers and a pistol in the office.

Please click here for a fact-check of the removal of the 28 mayors last month.