Frequently voiced claims about Turkey’s constitutional change bill

As Turkey is readying for voting on a constitutional change bill that replaces its current parliamentary system with a presidential one, there are many false claims being made

Turkey will go to the ballot box on 16 April 2017 to vote in a referendum on constitutional reform that foresees a presidential system for the country instead of the current parliamentary one. Although the bill text is easily accessible on the Internet and necessitates no further clarification, some widespread false claims continue to diffuse. Fact-Checking Turkey assembled those claims and fact-checked each of them correspondingly. But providing the reader with some background information beforehand might help them better understand how Turkey came to vote on a political system change.

The 2007 presidential elections: epitome of paralyzing the parliament

On 24 April 2007, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced then-Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul as the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AK Party) presidential candidate in his speech to the party faithful. But Turkish secularists were unwaveringly opposed to Gul’s candidacy because his wife was headscarved – which, they argued, infringed upon the laïcité of the Turkish state. Even before the AK Party announced its nominee, massive rallies known as Cumhuriyet Mitingleri (the Republican Rallies) were held to protest against the probable candidate of the AK Party amid coup threats from the army. Years later, organizer of the rallies Tuncay Ozkan apologized to the “people we scared” for his harsh secularist rhetoric.

Soon after the first round of the election in which Abdullah Gul was the winner, the army issued a statement on its website that came to be known as the “e-warning” where it said: “Arguments over secularism are becoming a focus during the presidential election process and the Turkish armed forces are following the situation with concern. It must not be forgotten that the armed forces are the determined defenders of secularism.” But the AK Party government did not leave this “warning” unanswered. In the statement it issued the other day, the ruling party said: “First of all, we would like to stress that it is unimaginable in any case in a democratic state observing the rule of law that the General Staff as an institution under the Prime Minister issues a statement against the government.”

Though Abdullah Gul secured all 357 votes in the first round of the presidential elections which used to be held in the national assembly of Turkey, opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) immediately applied to the Constitutional Court to annul the election, arguing that 367 MPs had to be present in parliament for the election to be valid. The court agreed and canceled the election. Because the AK Party did not have 367 deputies and other parties still boycotted the elections, the presidential elections could not be held. As a result of this impasse, the general elections were renewed and the AK Party’s vote rate soared from 34.2 to 46.6 percent. This time, with the backing of the right-wing opposition Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the presidential elections were finally complete in 28 August 2007 after four months of deadlock: Abdullah Gul was elected president.

The 2007 referendum: germ of today’s constitutional change

But all of this did not happen in vain. This story taught both the government and the people of Turkey a lesson – that the process of presidential elections should be reformed thoroughly. To that end, the AK Party penned a constitutional change bill which foresaw the president’s election by popular vote, allowed running for president for two terms, and reduced both the presidential and parliamentary terms from seven to five years and from five to four years respectively. The bill was repeatedly vetoed by then-President Ahmet Necdet Sezer who contended that “the constitutional amendment package is against Turkey’s parliamentary system and could cause instability” and ultimately decided to hold a referendum on the bill towards the end of the same year. The changes were accepted with the referendum resulting in 69 percent ‘Yes’ votes.

In 2014, Recep Tayyip Erdogan won the presidential election by 52 percent vote. President Erdogan became the first popularly elected president of the Republic of Turkey. But his election campaign was based on the promise that he will be a “sweating president,” invoking a Turkish phrase that denotes hard work. “Will you be head of the public and sit back? Such a thing is not possible. I will be a sweating president,” he said. The election of a politician as president by popular vote who promised to engage in politics actively fundamentally challenged the traditionally ceremonial role of the office and transformed it for good. The Turkish president was no longer someone who merely hosted official celebrations or signed documents. The president now constituted the very center of politics in Turkey – just as in the US.

What does the president’s election by popular vote mean?

One of the fundamental features of a governance system is the way the president is elected. In a parliamentary system the president is mostly elected by the parliament whereas in a semi- or full presidential system the president is directly elected by popular vote. When he said that the presidential election by popular vote was “against Turkey’s parliamentary system,” Ahmet Necdet Sezer was right in this technical sense. But once the Turkish people were asked if they would like to elect their own president and they answered positively, a discussion about systemic change ultimately became compulsory. Moreover, the limits of the novel de facto role of the president was not determined in the constitution.

There were two inevitable consequences of the 2007 referendum: (1) either the system would have changed into semi- or full presidential system or (2) have gone back to the parliamentary system. Although in theory Turkey still claims to have a parliamentary government, it would be indeed a “going back” because in practice it is not a pure parliamentary governance system anymore. The current political system in Turkey is rather a semi-presidential one because the president, who was endowed with many powers in the 1982 Constitution and moved to the center of politics since 2014, is being elected by popular vote while the head of the government is still the prime minister. To go back to the parliamentary system, the presidential elections should be returned to parliament but in such a case the people should be asked again if they would let go of this democratic right.

Now let us move on to the claims about the proposed amendments.

1) Claim: “The president will dissolve the parliament”

This is probably the most widespread false claim. However, in fact the president can already dissolve the parliament at the moment whereas the bill foresees the cancellation of this prerogative.

The latest example of the parliament’s dissolution by the president occurred in the 2015 general elections when the parliament failed to form a coalition government for almost three months after no party gained enough seats needed to form a single-party government. On 24 August 2015, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan decided to renew the elections without being affected by this decision. That is to say that he remained in power because his office was not subject to the decision of renewing the elections – which is why this practice was called “dissolution.”

But Article 116 of the proposed changes say that now the presidential elections should also be renewed if the president decides to renew the parliamentary elections. While dissolution requires by definition remaining untouched by the act of dissolving, the president’s office also will be affected by the parliament’s “dissolution” – which is why it can no longer be called dissolution.

The bill also foresees that the president, who can run for two terms under normal conditions and for an additional third term if the parliament renews the elections in the second term of the president, will lose the rest of the term in which they renewed the elections. This consequence of the decision to renew the elections implies that the decision can be made only in extraordinary circumstances.

2) Claim: “The president will decide the budget”

According to Article 161 of the amendments, the president cannot decide the budget but presents the budget proposal to the parliament and the parliament is to make the final decision. The article reads:

“The president will present the budget proposal to the parliament at least 75 days before the new fiscal year. The proposal will be discussed in the Budget Commission. The proposal text accepted by the Commission within 55 days will be discussed in the parliament and given the final decision until the new fiscal year begins. In case the budget law cannot be put into practice until the deadline, a temporary law will be made. In case the temporary law is also rejected by the parliament, then the last year’s budget will be used being increased at the rate of revaluation until the new budget proposal is approved. . . . The budget law cannot involve a prescription that says the spending can be exceeded by issuing presidential decrees.”

3) Claim: “Presidential decrees will have the force of law” or “The parliament is being rendered powerless” or “The president will rule by decrees”

Article 119 of the amendments say the president will have the right to issue decrees having the force of law (DHFL) during a state of emergency. At times other than a state of emergency, the president issues presidential decrees but cannot issue DHFL, which are different notions. In terms of the hierarchy of norms, laws/codes are superior to both DHFL and presidential decrees. Accordingly, the president’s right to issue decrees is restricted by five prescriptions in the bill. The related part of the article reads as follows:

“The President can issue decrees on subjects concerning the executive. The fundamental rights, personal rights and duties in the first and second divisions, and the political rights and duties in the fourth division of the second section of the Constitution cannot be regulated by Presidential decrees. The President cannot issue decrees on issues that the Constitution says will be specifically regulated in code. Issues which are conspicuously regulated by law are exempt from Presidential decrees. When a law and a Presidential decree have different prescriptions, the law applies. A Presidential decree is annulled when the parliament passes a law on the same subject as the decree.”

In the current parliamentary system, DHFL are issued by the Council of Ministers and are submitted to the parliament for discussion. If the parliament ignores the discussion, there is no legal consequence of this omission: the DHFL remains active. In the proposed system, a DHFL issued by the president is also presented to the parliament but if it is not discussed and given the final decision within three months, that DHFL is annulled. The related part in the same article reads as follows:

“Except for when the Grand National Assembly of Turkey cannot convene due to war and casus fortuitus, the presidential decrees issued in a state of exception will be discussed in and be decided by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey within three months. Or else, Presidential decrees issued in a state of exception will be canceled on their own.”

The parliament in the current system is dysfunctional to the extent that members of the parliament nearly play no role in processes of legislation other than voting for what is on the ballot. The underlying reason for this inaction is that 99 percent of laws passed by the parliament are drafted in the Council of Ministers and presented to the parliament as draft laws. As a result, most members of the parliament do not know of the content of the draft they voted into law.

The proposed system, however, abolishes the executive's right to draft laws. The only legislative proposal the executive would present to the parliament will be on the budget. This regulation will buttress the separation of the executive and the legislature, thereby emancipating the latter from the former's dominance. Accordingly, members of the parliament will also have to study the issues they want to present to the parliament as legislative proposals.

Moreover, the last sentence of Article 104 of the Turkish constitution authorizes the parliament to furnish the president with further powers by making new laws. The sentence states that "The President of the Republic shall also exercise powers of election and appointment, and perform the other duties conferred on him/her by the Constitution and laws." The uncertainty of "the other duties" of the president implies that the president could be granted any power in the current system.

4) Claim: “The vice president will become president if the president dies”

It is true that a vice president will become acting president if the office somehow falls vacant. However, unlike the US presidential system where the acting president occupies the office until the end of the term regardless of how close the next presidential elections are, the presidential elections should be renewed within 45 days in such a case. Which means that the presidential succession will not be tethered to the president’s personal will who might want to guarantee that someone close to them be the president after themselves. The Article 106 says:

“The President can assign one or more vice presidents after their election.

The Presidential elections will be held within 45 days in case the office of Presidency falls vacant due to any reason. The Vice President [determined in advance to be Acting President among all vice presidents] becomes the Acting President and exercises presidential powers until the new President is elected. If there is one or less than one year left for the general elections, then the elections of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey are renewed along with the Presidential elections. If there is more than one year left for the general elections, then the newly elected President remains in office until the elections of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.”

5) Claim: “The judiciary will be in the service of the president”

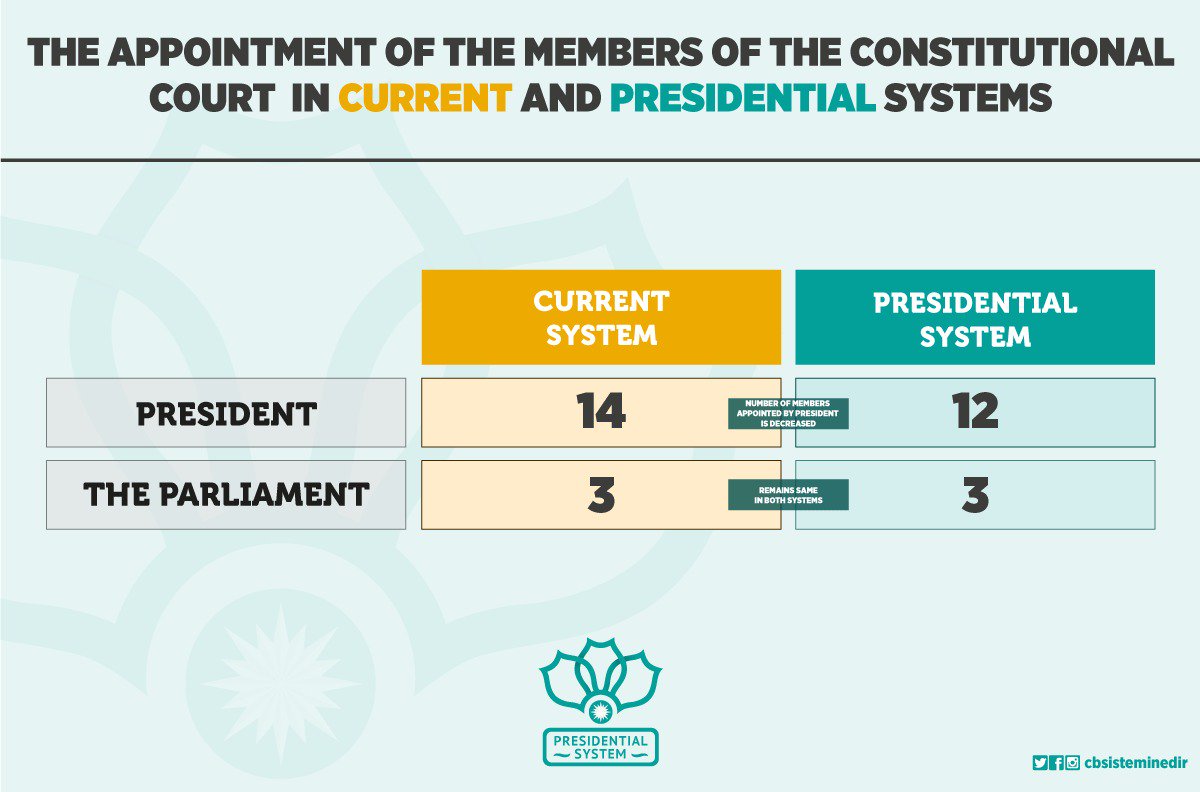

Although the number of high-ranking judges assigned by the president shrinks in total, the claim that the judiciary will be dependent upon the president is commonly voiced. The main point of this argument is that the president will assign 12 members of the Constitutional Court out of 15 while the remaining three will be elected by the parliament, hence the Court’s so-called dependence on the president.

The table shows that the number of members assigned by the president was decreased from 14 to 12, with two members of military origin of the Court being removed from membership. But more importantly, the Court’s members’ time in office far exceeds that of the president. After the constitutional change in 2010, the Constitutional Court’s members’ time in office was limited to 12 years which previously ended at the age of retirement, 65.

Given that a presidential term consists of five years, a president who is elected for one term will not be able to replace most of the members of the Constitutional Court. Technically, it is possible that a president can rule for almost three terms (around 15 years) by way of popular elections and can refresh the Court entirely. However, such an exceptional circumstance can but take place through democratic procedures.

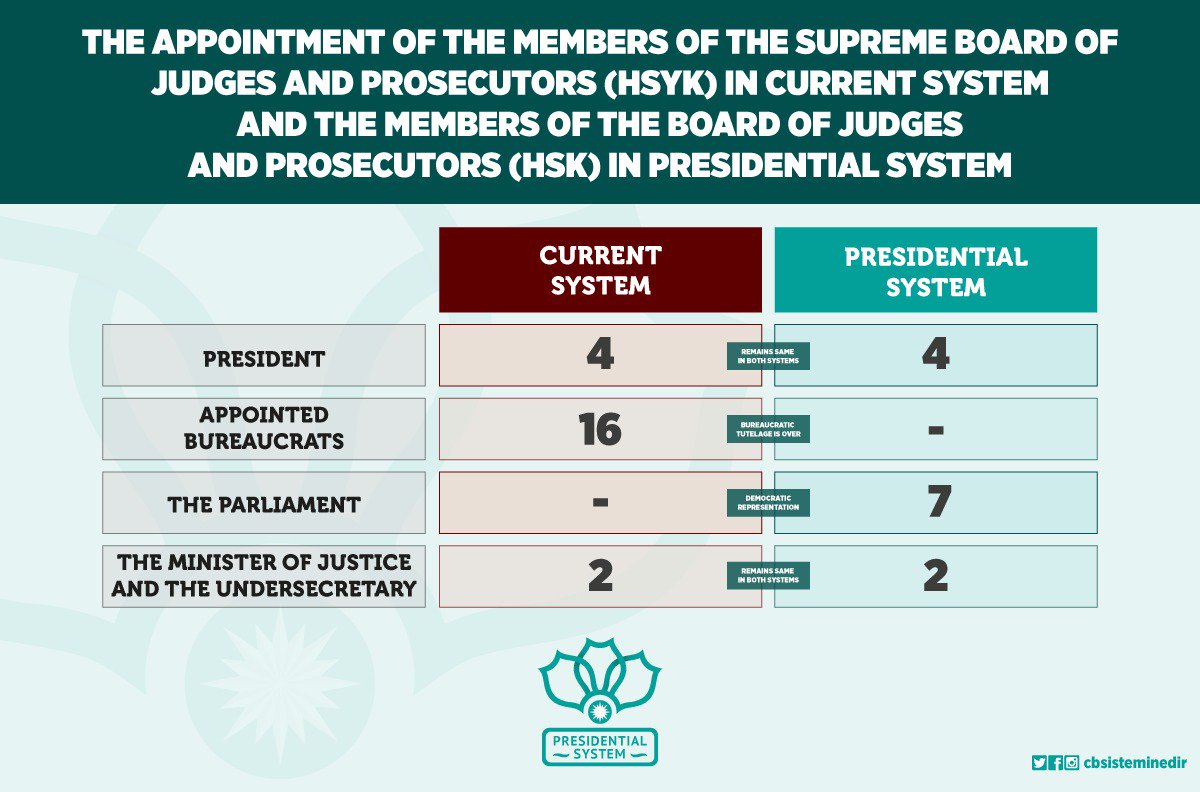

The other prominent judicial institution is the Council of Judges and Prosecutors (HSK) which was previously named the High Council of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK). The word ‘High’ was dropped because there were no other councils under the HSK to render it higher. The HSK used to consist of 22 members, 16 of which were appointed bureaucrats. The assignments of the HSK were taking place within a closed circuit of judicial bureaucracy.

With this constitutional change bill, the number of the HSK's members were reduced to 13 and the parliament was given the right to elect seven members of the Council, thereby opening the closed structure of the institution to the democratic legitimacy of the popularly elected bodies and offices. With the number of members assigned by the president remaining the same, the parliament will assign more members than the president.

6) Claim: “It will be impossible to impeach the president”

In the current system that was established after the 1980 coup, the president can be impeached only for treason. But a crime first and foremost needs to be defined by law in order for someone to be judged on account of committing it while treason was not even cited as a crime in the Turkish Penal Code. As a result, it is technically impossible to impeach the president in the current system.

The proposed amendments, however, expand the scope of the criminal responsibility of the president considerably, replacing the phrase 'high treason' with 'a crime'. According to the bill, it will be possible to impeach the president for any crime defined in the Turkish Penal Code, following the steps of the impeachment process. Article 105 explains how this mechanism, similar to that in the US, will work:

“It is possible to demand that an impeachment investigation about the President be launched on account that they committed a crime through a motion to be proposed by a vote of simple majority. The parliament must discuss the motion within one month and can decide to open an impeachment investigation with a three-fifths vote of the total members of the parliament in a secret ballot. . . . The Grand National Assembly of Turkey can decide to try [the President] in the Supreme Court with a two-thirds vote of the total members of the parliament in a secret ballot. . . . The President about whom an impeachment investigation has been launched cannot decide on renewing the elections. The incumbency of the President who has been found guilty of a crime preventing them from being re-elected will be terminated. This article also applies to the aftermath of the President’s time in office for the crimes they are claimed to have committed during their tenure.”

7) Claim: "Separation of powers will be abolished"

It is claimed that the separation of powers will be destroyed in the proposed system and the powers (the executive, the legislature and the judiciary) will instead fuse with each other under the office of the president. But there are serious measures stipulated in the constitutional change bill, some of which were already discussed above, to ensure the separation of powers. These could be listed as follows:

- Although both the executive and the legislature are equal in terms of their legitimacy deriving from being democratically elected by popular vote, presidential decrees will nonetheless be inferior to the parliament's legislations to establish the parliament's functional superiority over the executive. This also means that the executive will be prevented from interfering with the parliament.

- Correlatively, the president will have the right to veto the laws passed by the parliament. The purpose of this regulation is to hinder the legislature from paralyzing the executive by making laws that trespass on the executive realm, thereby nullifying presidential decrees.

- According to an article penned by a senior jurist, the president will be able to issue decrees in only six topics that concern solely the executive as opposed to 80 topics that the constitution says will be specifically regulated by codes – another aspect that further serves the separation of powers. Therefore, the president will be able to issue decrees to assign or remove vice presidents, ministers and high-ranking public officials (Article 104); to establish ministries and make changes to the structures of already existing ones (Article 106); to determine the organization and duties of the National Security Council (MGK) (Article 118); to create a legal entity (Article 123); to assign the Chief of General Staff (Article 117) and to regulate the State Supervisory Council (Article 108). It is also noteworthy that the US system allows the president to issue a decree on personal rights and freedoms whereas in the proposed system presidential decrees cannot penetrate rights and freedoms.

- Presidential decrees having the force of law (DHFL) will be automatically canceled if the parliament fails to discuss them within three months following their date of issuing. The proposed system thus continues to protect the functional superiority of the parliament over the executive. Moreover, DHFL in the current parliamentary system preserve their legal validity even if the parliament never discusses them.

- It will not be possible to take part both in the legislature and in the executive at the same time, unlike the case in the current parliamentary system. The membership of a member of the parliament will terminate if they accept to hold office as a minister.

- Any official within the executive, including the president, will be prohibited from presenting legislative proposals to the parliament, contributing to its independence.

- Article 9 of the constitution which reads "Judicial power shall be exercised by independent courts on behalf of the Turkish Nation," is amended by adding "and impartial" following the word "independent." As impartiality is the source of power and reliability of the judiciary, this amendment is predicted to increase the autonomy of the judiciary in the face of other powers.

- Military courts will be abolished. As a result, the judiciary will be further unified; the principle of natural judge will be fortified; and unfair rulings will be alleviated – all of which will help enlarge the autonomy of the judiciary.

- With military courts being abolished, the number of judges in the Constitutional Court assigned by the president will diminish by two. The parliament, which has no say in the current system as to the appointment of members of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors, will elect seven members while the 16 appointed bureaucrats of the council will be completely effaced. Consequently, the parliament will be reinforced before the executive and the closed bureaucratic structure of the judiciary, which has been effectively used as a tool of tutelage in the current system, will be pried open to the appointments of democratically elected politicians, making the judiciary a more democratic institution.

- The temporal gap between times in office of the president and the members of the Constitutional Court, explained above, will function as part of the mechanism of checks and balances between the two powers, curbing the president's ability to make appointments.